For those of you who don’t spend hours of your day staring at a screen, ostensibly trying to write but too often procrastinating and instead surfing the web like some people I could mention (*ahem*) the most recent hot topic you may not have heard about are NFTs.

It’s whatnow?

NFTs. Non-fungible tokens.

It’s whatnow?

Exactly.

As some of us have learned of late, “fungible” is an economic term for something that can be exchanged for an equivalent value of something else of the same type. A $20 bill is fungible because it can be exchanged for two $10 bills, which we all agree equals the same value. Whereas an original piece of art isn’t fungible because it doesn’t objectively equate to the value of other art that it could be exchanged for.

A token in this case is a term for a unique digital identifier indicating that there’s only one of it.

Put them together and you have a non-fungible token: A digital property that there is only one of.

That’s the part that has a lot of people scratching their heads. Digital items, by their nature, can be reproduced indefinitely. If I take a digital photo and make it available to purchase, I can sell that exact same image as many times as I want to as many people as I want. None are any more unique than any other, because they’re all literally the exact same item.

The difference with NFTs, the theory goes, is that if I made that original photo an NFT–as anyone can freely do with any digital property they own or create–and sold it, there would be only one unique version of that file.

That doesn’t help clear up the confusion, though, because… okay, so there’s only one original of it and no one else has that unique, first-of-its-kind file. But it can still be copied. People could see it online, if it’s made public, and simply download a copy of it for themselves. No, it wouldn’t be “the original” image, but it would be a replica of the original (if perhaps lower res, which most wouldn’t care about to look at something or have a copy on hand), and it would be free.

It seems the exclusivity of having that original first thing (infinite copy-ability be damned) would itself be the key appeal to owning an NFT.

Sound odd?

That’s because is.

Collectors have traditionally collected unique or rare, but always physical, items. But NFTs are creating a new frontier of people selling and collecting items that a) don’t physically exist and b) can be duplicated by anyone anywhere if they’re ever shown online.

One wouldn’t be alone in thinking that surely people wouldn’t have any interest in such a thing. A digital file? That anyone could simply copy for themselves, not caring if it wasn’t “the original” one if it’s just like the original anyway?

So it may come as a shock to you that not only has the NBA reportedly made $200 million so far selling NFTs–short video clips of popular basketball players making great shots–but what brought NFTs to light for many was the purchase in early March of digital artist Beeple’s piece “Everyday: The First 5000 Days” for US$69.3 million.

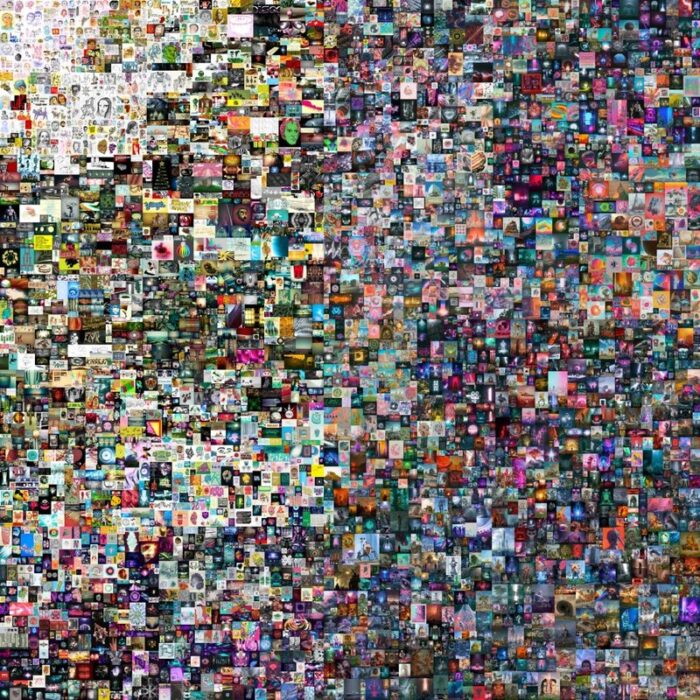

Here it is, by the way:

It’s a collage of artwork pieces he made every day for 13 years. Which is a cool idea, and all, but not, to this beholder, worth tens of millions of dollars. Particularly since, I’ll remind you, it doesn’t exist other than as a digital file. Which I just copied and posted here in part to make the point that anyone can copy it in its entirety for themselves and have the same “item” the original buyer does.

Meanwhile, as a comparison, for under $60 million (for the thrifty among us), one could get an original Picasso, van Gogh or Gaugin. Any guesses which way I’d go with that kind of scratch to throw at buying artwork?

I think writer and business executive Seth Godin called it properly when he said that NFTs are the new gold rush: A precious few who try to make, sell, or trade NFTs will actually make fortunes, while the overwhelming majority of those who try to won’t make a dime. Meanwhile, time, effort and energy–including, as Godin explains, literal electricity–will be spent in earnest in the attempt.

Beeple himself, the professional working name of Mike Winkelmann, has said that NFTs are a bubble. It’s probably wise to listen to the guy who’s at the very tip of the spear on creating and reaping the rewards from this new category of goods. If someone who’s making tens of millions off doing something doesn’t think the gravy train is going to last, people should probably take note.

But I suspect that despite his warnings and just the seemingly baked-in nonsense factor, NFTs aren’t slowing down any time soon.

In fact they’re still ramping up, now edging into real estate (virtual estate?), with it reported yesterday that someone just bought a $600K virtual house.

A bargain at twice the price? Sheer insanity? It’s all up for debate, of course. Personally, at the risk of sounding like an out-of-touch old man mumbling about how things made more sense “Back in my day”, I don’t mind saying that I simply don’t get the interest or appeal of owning NFTs. Buyers don’t own anything a harddrive glitch or power surge couldn’t erase, anyone can get a copy for themselves for free, a fool and his money, etc.

But having said all that, perhaps I’m being unfair to what NFTs offer and should give them a shot. So tell you what: If you want to buy an original piece of digital art, I’ve got a photo of some swampland in Florida I’ll sell you…

An interesting twist to this:

In talking with a friend about this article and NFTs more broadly, I created a bump in my own road of conviction against them.

Setting aside for the moment the sometimes crazy cost of high-end artwork–that’s another topic in and of itself–I don’t know that there’s a striking difference between paying for an NFT and paying for something like Netflix. Both give you access to something visual and perhaps even immersive, an entertainment or distraction of sorts, which you enjoy but don’t own a physical version of.

If I enjoying watch a half-hour sitcom on Netflix, and the buyer of Everyday enjoys looking at that artwork for half an hour (not that there must be a 1:1 ratio of eyes-on enjoyment, but just as an example), why is paying for one deemed totally normal and paying for the other deemed outlandish?

I suspect, and again not to get too far into it, that price is a big part of the perception. If I paid a 3D artist their hourly rate to create a virtual house for me, that would certainly (at least to me) seem more normal than paying $600K for it. It seems likely that at its core, it’s the extraordinary price paid, not the owning of something digital, which makes the NFT situation raise eyebrows and drop jaws.

If the mystery buyer of Everyday had purchased it for $474,500–$100 for every day of artwork in the final piece… or even double that to almost a million bucks–would there be less controversy than his paying almost $70 million? Because if so, then it’s a very different discussion from the one people seem to be having about this issue.

Definitely some different takes on it for me to noodle on.